History of Italian Food

The nascent history of Italian food began about 13,000 years ago and firmly established itself when the Etruscans, Greeks and Romans moved into the Italian peninsula around 1,000 BCE. By about 400 BCE the Romans, either by assimilation or conquests, had taken control of this racially, culturally and linguistically diverse area.

Early Italian cuisine revolved around barley or wheat, cooked into a porridge [puls] that was occasionally enhanced with wild greens, root vegetables, fruit or for a really big celebration perhaps a little honey. The ever-expanding boarders of the Roman Empire provided spices like cumin, sesame, coriander, oregano, olive oil and saffron to those who could afford it. The legionnaires of Rome marched off to war with a bag of barley and salt hanging from their furca that they would later boil up with whatever else they could forage or commandeer in the field. After conquering Macedonia around 200 BCE the returning standard bearers brought commercial baking to the city of Romulus and Remus enriching the history of Italian food and making bread the staple of the Roman welfare system called the Annona. These public bribes … think bread and circuses, cum welfare programs were an important part of Rome’s public policy for the next six centuries and helped shaped the history of Italian food.

Italian Video Recipes can be accessed by clicking on the above recipe tabs in the header

Italian cuisine, beginning with Rome, was influenced by the Greeks who in turn were influenced by the Persians. Although no known Greek cookbook exists in its entirety the portions of those that do cite simple cooking techniques such as frying or open roasting and utilized cheese or oil as a sauce. Our only knowledge of Roman cuisine comes from a gourmet, or a group of author/cooks, writing under the name of Apicus in the first century CE whose advice remained the go to source throughout the middle ages. The most striking common ingredient was a condiment called garum, or liquamen, a fermented/putrefied fish sauce like that of Indochina, along with ample amounts of honey, herbs, spices and olive oil. Some theorize that the Roman elite, especially towards the end of the empire, suffered from lead poisoning en masse and therefore used culinary amendments to excess so they could taste their food. The Romans used lead to line their cooking and storage vessels, the famous amphora jars used for wine and olive oil transport, and several of the 11 aqueducts that brought over 100 million gallons of water a day to Rome for its fountains and sewage system and they also used an additive/condiment that had huge amounts lead in their food and wine. Granted the theory is conjectural but it certainly adds to the speculative reasons for the empires demise.

A variety of amphora’s used for liquid and grains.The pointed end allowed them to be stuck in sand for sea travel

The city of Rome, with over one million inhabitants at its apex, obtained all its provisions from the imperium’s other 60 million second class citizen spread throughout the far-flung empire. Life for the city’s privileged was great but squalid for the other 600,000 poor whose du jour menu of bread, garlic, oil, wine and barley was 24/7 and mainly supplied by the annona. If you were fortunate to have a few semuncia, valued at about 10 cents, you could purchase a grilled sausage, a bowl of roasted chick peas or a plate of salted fish from one of the many street vendors or thermopoliums [predecessor to fast food] but in most cases only the middle class and their betters could avail themselves of this street food since few had any hard currency. Power in Rome required controlling the proletariat so the nobility administered the bread and circuses of the annona that doled out food, mortal combat, wine, wild animals, chariot races, baths, theater and olive oil to entertain and hold the mob in check. The use of rare spices and exotic proteins were signs of status and prestige for the elite banquet where the copious use of cinnamon, nutmeg, mace, cloves, pepper, ginger, anise, paprika, cardamom, parsley, sage, mint, marjoram and dried mushrooms was common. A gourmet pantry included 54 cultivated and 43 wild vegetable varieties along with figs, apples, pears, and a selection of sprouts and seeds that included marijuana. Farmed oysters, fish, and eels as well as fine olive oils, crusty breads, sausages and vinegars rounded out the trendy menu for the foodies. But the man on the street still lived with a grumbling stomach only occasionally placated by a gruel of barley with a soupcon of onion, garlic or leek for flavor. The annona might dispense a slice of bread, a little olive oil, a few olives, a little fish sauce and once in a while a dried fig but it was an occasion not a state. In early Italy wine was basically the only liquid consumed unless you couldn’t beg, borrow or steal a draught and had to resort to water. Furthermore wine, except for a full strength shot to begin your day, was always amended or diluted for flavor, bouquet or extension and often had seawater added to prevent it from turning to vinegar and most interestingly the arguable debilitating addition of a grape must reduction called defrutum, carenum, or sapa {more on this later]. Fine wine was cataloged by using the emperor’s reign as its vintage while the brew of the masses had no date or no age and took only three months to ferment from left over seeds and skins. The plain Roman citizen imbibed this “cold duck”, or perhaps just a little vinegared water, to wash down his or her daily barley puls unless you found a few coins rattling around in your money bag … no pockets.

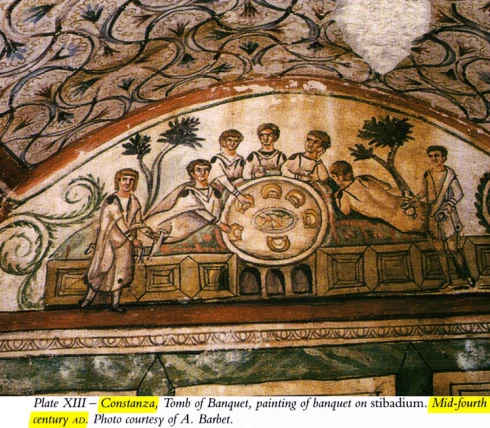

Today we lovingly like to represent the last period of the Roman Empire with gormandizing, licentiousness and perversity but you had to be really wealthy to have that kind of fun. One myth tell us about the debauched nobility who would take an emetic break and visit the vomitoria in the next room before returning to the dining couch for more. But linguists aren’t sure whether the reference actually meant a room or instead applies to an exit, like a gate or hallway in a stadium … in any case it sure adds color to the image. Who doesn’t relish in the accounts of Cleopatra roasting eight boars at a time so one would be just as Marc Anthony dinner would just as he liked it when he got home or those great scenes in the Hollywood B movies showing the demented emperors eating grapes and groping slave girls or boys. Historically the Roman senate did pass laws limiting the number of guest you could host, the types of exotic protein you could serve and the amount of money you could spend on your soiree because it had gotten out of hand. But the affected hosts were the billionaires of their time and you had to either be one, or at least part of their retinue, to participate in one of these legendary and historic bacchanals. Even though numerous writers and philosophers of the period bemoaned these debased and indulgent displays they were surely only a once or twice in a life time event for anyone but the A list glitterati. It’s also prudent to remember that just as Roman conquests advanced food production technology they also introduced new cultivars and foodways into the Mediterranean diet that still resonate today.

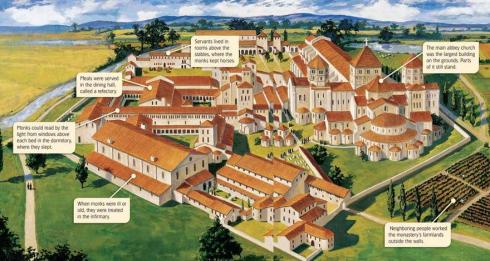

The social pundits of the day maintained that the exorbitant use of spices in Italian food drained the treasury and distorted the balance of trade in favor of the East since all these products had to be imported from that area. But even with this public reprimand the privileged continued their penchant for the rare and exotic until the Vandals, Goths and Visigoths finally brought Rome to its knees in the fifth century. When the empire tanked it took the Italian diet with it and it didn’t matter if you were rich or poor. The long-established trade routes of the Pax Romana were taken over by the Arabs and it was back to barley and wild greens for everybody. During the next 600 or so years the area was invaded, controlled and abandoned by the Byzantines, Saracens, Franks, Normans, and the Papal authority established by Charlemagne in addition to being visited by a number of plagues and famines. During the dark ages the church acted as the only tether of stability and literacy and each regional bishop wielded their own army and justice system. Monastic scribes recorded the nuances of daily commerce and life, maintained libraries that preserved the knowledge of earlier cultures and, perhaps more importantly, kept wine, bread and cheese making technology alive. And at almost any monastery a hungry traveler could trade his soul for a bowl of minestra, a slice of bread or a little healing and a payer

So during the dark ages the mostly rural and plague savaged population eked out a caloric deficient diet in the hills and forests until the Norman occupation when many southern cities in Italy doubled in size. During the next three hundred years the pope’s Vatican barrio and the city states of Venice, Florence, Milan and Genoa became wealthy as the trade conduits between Islam, Byzantium and Asia. The crusaders of the period, who used the ships of Venice and Genoa to travel to and from the Levant, brought back many new cultivars and ideas on their return trip which quickly integrated with the foods of Europe. Granted many of these preciosities were being used by the Moors occupying Spain and rich Italian trader/merchants involved in trade but many of Europe’s elite from other areas were unaware of this bounty. Imagine your life without rice, coffee, sherbet, dates, apricots, lemons, oranges, sugar, ginger, melons, rhubarb, mirrors, carpets, cotton cloth for clothing …THINK UNDERWEAR …, ships compasses, writing paper, wheelbarrows, mattresses and shawls, chess, Arabic figures 0 to 9, pain killing drugs [milk of the poppy], algebra, irrigation, chemistry, the color scarlet, water wheels and clocks, candy, the lute, harp, carrier pigeons, donkeys, olive oil, pomegranates and many more new wonders.

Even during the fourteenth century an estimated 94% of all Italian food consisted of barley, oats, rye gruels or bread and wild, read foraged, greens or fava beans while the upper classes feasted on domestic protein spiced with newly introduced and imported exotic items and expensive leavened wheat bread. The Black Death of 1350 swept away more than half of the Italian peninsula’s inhabitants who were already suffering from famine … the effects of a little ice age that lasted until the middle of the nineteenth century. When the English defaulted on numerous loans owed to the large Italian banking-house, and the Ottoman Turks usurped the trade routes and their attached territories in the Aegean, Italy turned in on itself. Unstabilized fractions aligned with either the Pope or the Holy Roman Empire and for the next hundred years or so mercenary Swiss and German forces fought for different city states as the already underfed population continued to increase. This post plague population boom concordantly increased the demand for goods, services and foodstuffs that created a growing middle class of providers. The churches inability to intercede and assuage the ravages of the plague, cholera and typhoid coupled with the waning of the feudal-serf relationship provided and excellent medium for the social, intellectual and culinary growth of the Renaissance.

The newly enfranchised merchant, commercial and artisan classes began to make loans to the old guard who, without a feudal-serf base to support them, soon began signing over their assets; palacio’s and land in default. New sea trade routes of the Renaissance brought tangible goods, histories, literature and knowledge from the many cultures they connected. Soon Greek and Arabic texts were translated into Latin and, with the help of Gutenberg’s new movable type technology, diffused throughout the Italian peninsula spawning the “new” philosophy of humanism that influenced the thought, action, and foods of the period. The writing of these other and often ancient cultures, especially those of our old Greek friend Galen, inspired the medical/food based humors of the Renaissance with the earlier Greco mantra of wet/dry food and hot/cold disease. The emerged merchant and artisan nouveau riche flaunted their increased wealth and started living large, dressing well and adopting the joys of consumerism as their daily devotional. Printed cookbooks, based on earlier Greek, Persian and Roman texts appeared for the literate professional cook and the countess or count of the villa. These tomes had no measurements and recipes were to be constructed based on personal preference since a man or woman of quality knew how a dish should taste. There were no cooking times, few kitchen clocks existed, and so cooking intervals were often calibrated by the duration of prayers since everyone knew their devotions literate or not … Bake a fair-sized capon with almonds and honey for three Hail Mary’s and six our fathers or maybe roast a boar with apricots from vespers to morning prayers.

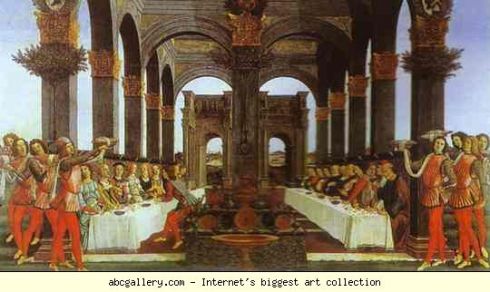

Some Italian bellies were beginning to fill but hunger was still a constant, not an occasion, amongst the rural and urban poor. The disparity between the urban poor and those of better means was punctuated by frequent food riots while the rural peasants continued to starve as they had for centuries before. New trade venues created commercial markets that help to ferment the many banking, trade, labor and insurance organs we now take for granted and the gold florin became the international currency. The new power elites, like the Borgia’s, Medici, Sforza’s, d’Estes and various doges were on the rise, making the uneasy familiar alliances that have become the lore of the Italian Renaissance, as they jockeyed for Papal and regional control. To legitimize their new positions of wealth and status they gave lavishly to support literature, science, dance, education, architecture, and Italian food and these efforts raised many a middle class craftsman or artisan to the ranks of the respected and sought after. It was during this period that the psycho popes began hosting their mind-boggling orgies and meals at the Palace of the Vatican while most of the rural, and at least one-third of the urban, population existed on barley, polenta or Arborio rice 24/7/.

Italian food history has been shaped by inputs from the Greeks, Romans, Etruscans, Vikings, French, Germans, Persians, Austrians, Goths, Normans, Turks, Hebrews, Arabs and Asians over a thousand years either through occupation, alliance or trade. Arab inspired walls were built around Italian villas to protect fruit and citrus trees from hungry animals and pesky peasants which spawned the design of Italian gardens. Persian technology was used to irrigate fields of rice, eggplant and spinach. Frugal Italians borrowed the new world pumpkin and used it to make faux shaped liver, fish and steaks that were then breaded and sautéed and the Italians use of vegetables swayed Europe’s elite from high levels of meat consumption and chronic gout to a more Mediterranean diet.

The historical underpinnings of French cuisine originated in Italy and if the peninsula’s foodways hadn’t undergone such post Renaissance deprivations Italian food would probably have become the haute of Western gastronomy instead of the codified Gallic mode. Since Roman times the Northern and Southern areas of Italy have differed in terms of culinary, social and technological benchmarks. Northern Italy has always been the richer industrialized region while Southern Italy has always existed as a poorer agricultural area whose frugal inhabitants invented some of the quintessential dishes we think of as Italian American food. Tomatoes, beef, lamb, butter, pork, pasta, olive oil, bread, rice and polenta were always regional pointers and social indicators until they migrated to the new world to fuse into what we think of as todays American Italian food. In the old country seasonal scarcity defined the Italian family’s nutritional regime, and, unless you where wealthy, meals were for the immediate household, think the archetype meals of the godfather and other Hollywood crime family tropes, only because social convention made reciprocation in spades an ingrained part of daily interaction.

One very interesting theory holds that the Italian, and actually the European, diet of the last millennia was so lacking in complex carbohydrates, protein and caloric inputs that it barely fueled simple metabolic functions. This Italian food hypothesis supposes that the diet was made up of toxic plants, rotted food and breads made from flours blighted with hallucinogenic {LSD is a synthetic derivative} ergot fungus aka St Anthony’s fire or dancing mania. This supposition when combined with the constant parasitical infestations and endemic lifelong malnutrition explains the dreamlike state that most people existed in and the religious, folkloric and superstitious specters of the period… dragons, witches, angles, demons and unicorns OH MY! Pasta has been Italian since 400 BCE but only for the wealthy since it was made from milled grain and therefore it’s not surprising to discover that few natives experienced this iconic Italian American food until they got to the US. Pasta machines appeared in Italy, along with wind and water powered mills, in the eighteenth century but the average Italian was far more likely to have enjoyed a bowl of pasta water from the villa instead of a plate of noodles and instead relied on barley, rice or polenta, in the south, as a dietary staple. A two millennia mélange of different cultural inputs accounts for the fragmented regional Italian food differences in meats, breads, pastries, pastas, cheeses and a hundred other groupings. These subtle differences can only be experienced in situ over a life time and we’ll only concern ourselves with the essence of American Italian food as we know it. Italians still lived primarily on cereals and legumes flavored with some wild weeds, salt or perhaps a few pieces of salted fish right up to the twentieth century. Foraging was an input source and much was written about Italian immigrants gleaning abandoned city lots for bird and animal deposited wild crops in New York City of the early 1900’s.

Bread at every meal and meat more than once a day was something that late 19th century Italian immigrants would write home about …. Only the rich could afford these luxuries in the old country especially the white Wonder bread variety that was so commonplace in the US. Italians brought us salads dressed with oil and vinegar, not the cooked dressing of America, and taught us that fresh herbs belong in the salad mix not the Wishbone dressing and the course is always escorted by good crusty artisan bread dipped in fruity virgin olive oil. Vegetables should be simply oiled or broiled often reheated with a little garlic, vinegar, hot peppers, salt and a liberal splash of ubiquitous virgin olive oil. Asparagus and artichokes are the stellar vegetable choice and although a huge favorite of the Romans they kind of got lost in the dark ages and where then rediscovered by the humanists of the Italian food Renaissance. As a child in California I always looked forward to grass and choke season and one of my favorite Hal Roach Little Rascal shorts features an artichoke, Alfalfa, Buckwheat and a whole lot of confusion. In California broccoli rabe, peppers, spinach and a variety of mushrooms – roasted, baked, broiled, boiled, sautéed or pickled became Californian Italian, and then national, standards. Of course many of us were raised on Chef Boyardee Ravioli, Franco American Spaghetti, and Appian Way Pizza mix in a box but as we matured so did are taste buds. Although some of us are still disciples of The Olive Garden I-Tal-Yan, many of are now conversant in the nuances of olive oil and California has its own domestic olive oil industry remembering that it takes anywhere from five to twelve years to produce fruit/oil.

Italians still tethered to the peninsula consume sixty pounds [great interactive pasta chart here] of more than 350 diverse pasta shapes a year while Americans slurp down a paltry 20 pounds annually. Italian pasta makers use softer flour for their pasta that cooks quicker, absorbs more sauce and has a different mouth feel than our domestic variety. Many food anthropologists think the fork was invented to pick up steaming, heavily sauced strands of pasta that were the Italian equivalent of the American Sunday roast and the device was then passed to the court of Henri II when Catherine de Medici became his bride but that remains to be proven. True Italian pasta sauce is meant to be a light embellishment for the noodle not a gloppy, thick meat laden or creamed sludge. Instead just a little exceptional virgin olive oil, some fresh herbs, roasted vegetables or maybe a little rosemary chicken with some freshly grated Parmesan and a splash of balsamic vinegar is as good as it gets. Depending on which region you’re examining polenta or the short grain Japanese rice known as Arborio often substitutes for the pasta. Italian food doesn’t rely on the large portions of animal protein favored by the rest of the Western world and its preparation method differs from region to region in fact in early Rome meat consumption was usually limited to animals sacrificed to the gods and not a common repast. Fish is served whole or portioned often on the bone and can be broiled, baked, steamed or lightly battered and fried.

Pizza, one of the worlds most well-known Italian exports is rooted in the flat breads served by many cultures throughout the world. My favorite Italian food myth is that the legions of Rome became fond of the matzoh bread served them in the Levant and their efforts to reproduce it morphed into the ancestor of today’s pie. Milk from the imported Indian water buffalo became Mozzarella that when combined with new world tomatoes and subjected to a few minutes in a hot wood fired oven created gustatory magic. The archetypical celebratory Italian meal of the past does not occur today except for the most festive of occasions. When it does it usually consists of something like this with each course served separately.

-

Antipasto; cold or hot appetizers

-

Primo; hot pasta, soup or vegetable

-

Secondo; beef, lamb, pork, chicken, fish or veal

-

Contorno; salad or vegetable

-

Dolce; dessert

-

Caffe; espresso

-

Digestivo; brandy, grappa or amaretto

Here’s another droll video from the History Channel “Food Tech”

http://www.history.com/shows/food-tech/videos/food-tech-italian-dinner#food-tech-italian-dinner